Diagnosis

Optic nerve drusen, both eyes

Discussion

Definition

Optic nerve drusen (OND), also known as optic disc drusen (ODD), is present in approximately 0.3% - 2.4% of the population. Drusen represent the accumulation of small proteinaceous material, which can deposit in the eye and become calcified with advancing age.1 The exact cause of OND is not certain, but it is suspected that abnormalities in optic nerve axonal transport and metabolism may play a role in their formation.2 OND are also often familial, with family members having a ten times increased risk of harboring an OND.12

OND commonly leads to peripheral visual field defects, however, these defects are often asymptomatic. In cases where patients experience symptomatic visual field loss or, rarely, loss of central acuity, we need to consider drusen-associated anterior ischemic optic neuropathy or a retinal vascular occlusion.1

OND is frequently discovered incidentally, either through automated visual field testing, which commonly reveals inferonasal abnormalities, or during a fundoscopic examination that shows an abnormal “swollen” appearance of the optic nerve. OND can present superficially or deep. Superficial drusen typically manifest as a “lumpy” appearance to the optic disc. This irregularity can often result in a “swollen-appearing” optic disc with indistinct and irregular disc margins on fundoscopy, which may be clinically indistinguishable from mild optic disc edema. Conversely, buried drusen are not typically visible on fundoscopy, and the optic disc can appear normal, swollen, or atrophic. In all cases, OCT can further support the diagnosis. On OCT, OND can be identified with a hyperreflective boarder and hyporeflective core.

While most cases of optic nerve drusen are often isolated, it is important to note that OND can also be associated with other conditions, including retinitis pigmentosa, angioid streaks of the retina, Usher syndrome, Noonan syndrome, and Alagille syndrome.1

Differential Diagnosis

1. Pseudotumor cerebri

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), also known as pseudotumor cerebri, is a condition characterized by increased intracranial pressure (ICP) in the absence of an identifiable secondary cause such as tumors, venous sinus thrombosis, or meningitis. This increase in ICP leads to papilledema, which can sometimes be confused with the swollen-appearance from optic nerve drusen.

IIH is relatively rare, presenting in only ~0.001% of the general US population. Its prevalence is higher among women, who are about three times for likely to develop the condition compared to the general population. Additionally, overweight women face a significantly increased risk, being approximately 20 times more likely to develop IIH than the general population.

This condition commonly presents with symptoms of headache, visual disturbances, and pulsatile tinnitus; however, symptoms can vary and patients may even be asymptomatic. On fundoscopic examination, signs of IIH include optic disc swelling and the absence of spontaneous venous pulsations (SVP). Visual field testing can also be used to help identify any defects associated with the papilledema.

Diagnosis of IIH is confirmed through cranial imaging, typically magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance venography (MRV), to exclude other potential causes of the increased ICP. Additionally, a lumbar puncture (LP) is performed to confirm the elevated ICP and to ensure normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) composition.

Management of IIH focuses on reducing ICP to alleviate papilledema and prevent permanent vision loss. Weight loss is a critical component of treatment in patients with obesity, which is the main identifiable risk factor for IIH. Pharmacologic treatment often includes medications such as acetazolamide to lower CSF pressure. In severe or refractory cases, surgical interventions may be required, including options such as ventriculoperitoneal shunt, lumboperitoneal shunt, optic nerve sheath fenestration, or venous sinus stenting.3 Aside from obesity, other risk factors for IIH include certain medications such as tetracyclines, retinoids, and corticosteroid withdrawal.6 Therefore, a thorough patient history, including a review of medication use, is essential for effective diagnosis and management.

2. Myelinated Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer

Myelinated retinal nerve fiber layer (MRNFL) refers to retinal nerve fibers that inappropriately possess a myelin sheath, unlike the normally unmyelinated retinal nerve fibers.7 Typically, myelination of the optic nerve does not extend past the lamina cribrosa into the retina. However, in cases of MRNFL, myelination passes this anatomical boundary and is readily detectable on a dilated fundus exam as white or gray fluffy patches that obscure the underlying retinal vessels and disc margins.7

MRNFL is a relatively rare congenital anomaly, occurring in less than 1% of the population, and is generally benign. It is usually unilateral, although bilateral involvement is observed in around 7% of affected individuals.7 Diagnosis of MRNFL is primarily based on findings from a fundoscopic examination. Ancillary imaging techniques such as optical coherence tomography (OCT), can further support the diagnosis. On OCT, MRNFL presents as a thickened and hyperreflective retinal nerve fiber layer. Infrared and red-free imaging modalities can also be used to visualize MRNFL.8

While MRNFL is typically benign and does not require treatment, routine follow-up examinations are recommended to monitor for any associated conditions or changes.7

3. Tilted optic discs

Tilted disc syndrome (TDS) is also known as “Fuch’s Coloboma” is a congenital abnormality that occurs in 1 – 2% of the population. It is frequently associated with high myopia, with around 20% of patients exhibiting more than 5 diopters of myopia. 9 Diagnosis of TDS can usually be made based on the characteristic appearance of the optic disc during a fundoscopic examination, which reveals an oblique orientation of the optic nerve head. This oblique insertion results in an asymmetrically elevated disc which can mimic optic nerve swelling.

TDS may also be associated with other ocular findings, including inferior or inferonasal peripapillary crescent, situs inversus, and inferior staphyloma. The gold standard for diagnosing TDS is optical coherence tomography (OCT), which provides precise measurement of the retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and can detect any tilting or abnormal shape of the optic nerve head.9 While visual field testing, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also reveal optical abnormalities associated with TDS, these modalities are generally not required for diagnosis.9

TDS does not require treatment. However, regular follow-up examinations are recommended to monitor for potential complications such as retinal pigment epithelium atrophy, choroidal neovascular membrane, subretinal fluid, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, fovea plana, retinoschisis, and lamellar macular hole. 9

Examination

i. Ancillary testing plays a crucial role in differentiating optic nerve drusen form potentially life-threatening optic disc edema. In clinical practice, visual field anomalies from optic nerve drusen usually become evident before the patient experiences any subjective vision loss. Typically, visual field defects related to OND manifest predominantly in the inferonasal quadrant, though can result in any pattern of optic neuropathy field loss depending on the location and extent of the drusen.

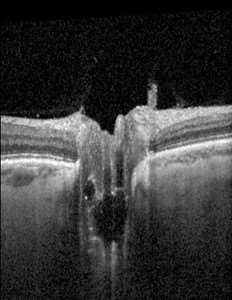

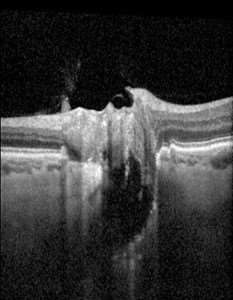

Superficial OND can typically be easily identified as round deposits in ophthalmoscopic examination. The diagnostic gold standard for both buried and superficial drusen is optical coherence tomography (OCT) with enhanced depth images (EDI). OCT with EDI provides cross-sectional images of the optic nerve head and enables visualization of the deep optic nerve layers, thereby facilitating the detection of both surface and buried drusen. Additionally, OCT can measure the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber lay (NFL) thickness to evaluate any NFL thickening or loss associated with drusen. 10

Alternative diagnostic methods include B scan ultrasonography, which, despite being cost-effective and rapid, is limited by its lower resolution and inability to assess the neural retina. Fundus autofluorescence imaging, while convenient for imaging calcified superficial drusen, is not able to detect buried drusen. Computer tomography (CT) may occasionally incidentally reveal calcified drusen but is not routinely used to investigate OND.10

Treatment

There is no proven effective treatment for OND. Fortunately, patients generally have a relatively favorable visual prognosis with this condition. Some studies have suggested intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering medications may be beneficial in cases of drusen-associated optic neuropathy by potentially preventing further visual field progression.11 However, due to the lack of robust evidence supporting the widespread use of such treatments, IOP-lowering medications are not routinely prescribed for patients with OND. Additionally, there is currently no established role for surgical resection of optic nerve drusen.